The appearance of small groups of Eurasian beavers (Castor fiber) in various areas of the Italian territory has attracted the attention of the scientific community. The return of this species after more than five hundred years of absence and its ability to change the landscape highlights the potential for coexistence with a wild animal species relatively unknown in Italy.

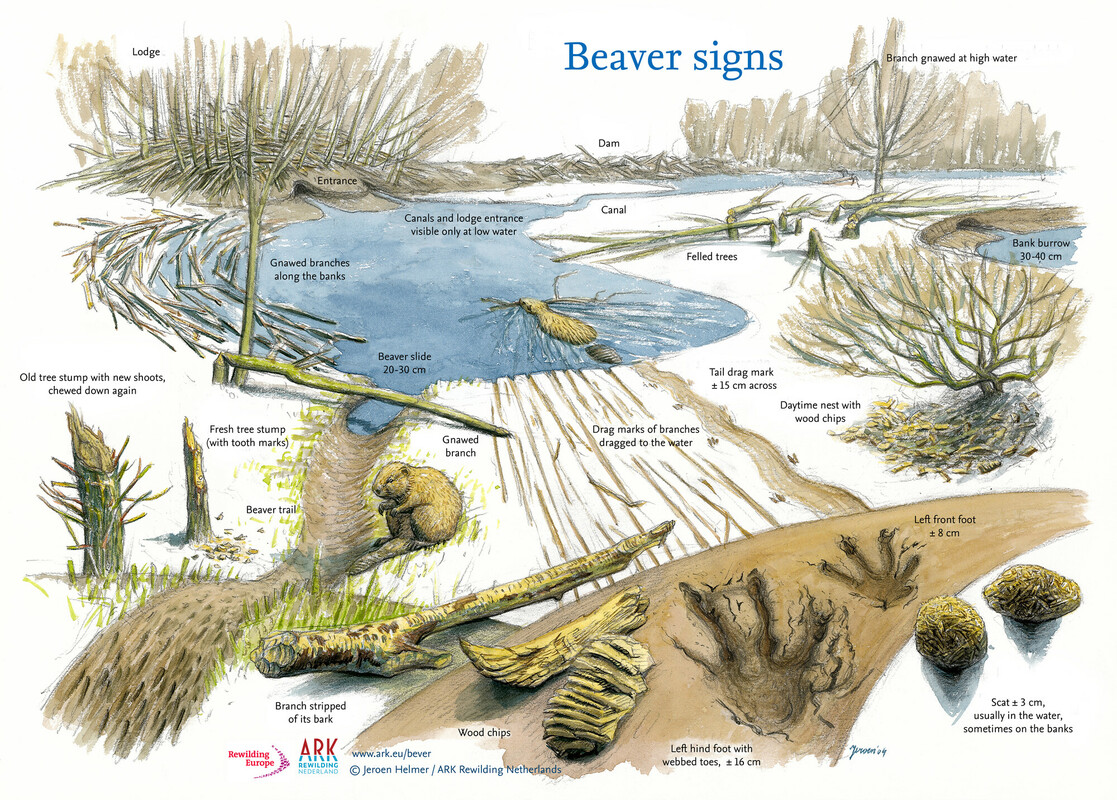

Gnawed trunks, dams and downed trees: the presence of the Eurasian beaver is unmistakable, to say the least. The combination of these signs of presence together with the images obtained from camera traps and genetic analyses on hair samples has confirmed that the species now lives in different areas of Italy: the north-east, in Friuli-Venezia Giulia and Alto Adige, near the Austrian border; the center of the peninsula in Tuscany, Umbria and Abruzzo; and in the southern regions of Molise and Campania. All of these areas are a great distance from each other, suggesting that while beavers have naturally come back from Austria – following official reintroductions there – unofficial releases have taken place in the center and the south of Italy.

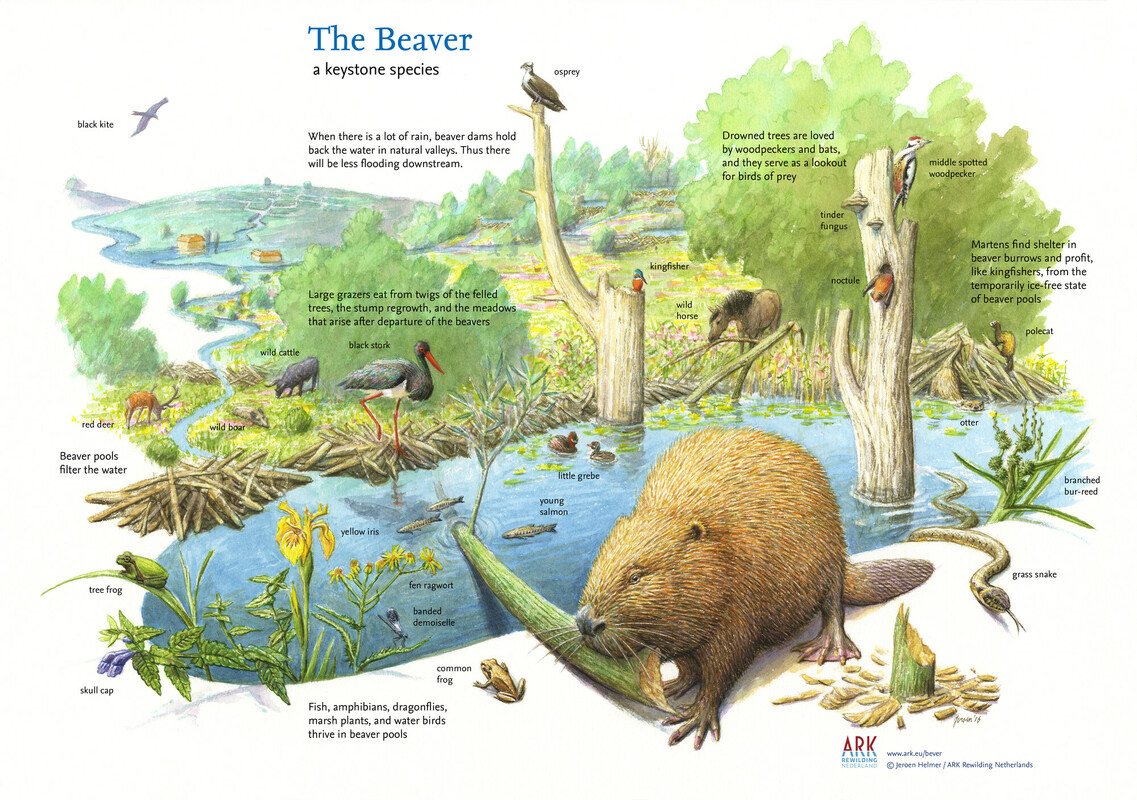

Beavers are known to be ecosystem engineers, capable of making major changes to the territories they inhabit, increasing biodiversity and improving the health and functionality of waterbodies. They are guardians of the natural environments whose presence can only be beneficial.

The history of beavers in Italy

The Eurasian beaver is a medium-large rodent native to all of Europe, including Italy. Humans have always been interested in beavers as a source of meat, fur, and castoreum, the oil produced by the animals’ anal glands, which makes their fur waterproof and is highly appreciated in the cosmetic industry. Due to hunting, the species underwent a strong decline in Europe after the Middle Ages, and in the 15oos and 1600s it was considered extinct in some countries, including Italy.

Since 1920, the beaver population started to recover in most of its original range thanks to legal protection and successful reintroductions, together with its natural expansion. Currently, there are around 1.2 million beavers in Europe, according to the European Wildlife Comeback report (2022).

The first sign of beaver presence in Italy was recorded in 2018 in the north-eastern region of Friuli-Venezia Giulia, most likely due to natural dispersal from Austria, where they had been officially reintroduced in the 70s. In November 2020, two individuals were seen on a camera trap in Alto Adige, once again near the Austrian border. A few months later, in March 2021, wildlife managers and some members of the provincial police noticed unequivocal signs of beaver presence in two areas of central Italy: on the border between the provinces of Grosseto and Siena (Tuscany) and between the provinces of Arezzo (Tuscany) and of Perugia and Terni (Umbria). The fact that these areas are located about 550 km south of the Austrian border suggests that, unlike the previous cases, unofficial releases have taken place in the center and south of Italy. Between January 2022 and March 2023, the number of signs of beaver presence reported by citizens and professionals increased. In April 2022, beaver presence was recorded in the north-east of Italy in the plains of the Po River, near the towns of Trino Vercellese and Fontanetto Po (Piedmont). In the same region, in March 2023, beaver presence was reported in Migiandone (Eastern Piedmont). In the same period, gnawed trunks were detected in the Volturno River in southern Italy, in the municipalities of Monteroduni and Roccaravindola (Molise) and Capriati a Volturno (Campania) testifying the presence of the southernmost beaver population in the world, which also corresponds to the southernmost record of this species in the Middle Ages. Lastly, camera traps placed for an otter (Lutra lutra) survey recorded beaver presence in the Aterno River (Abruzzo).

Since the next closest family of beavers lives 150-200 km north of the Aterno and Volturno rivers, in completely different water basins, scientists highlight that beavers must have been reintroduced by humans in this part of Italy. Therefore, the appearance of the Eurasian beaver in Abruzzo and southern Italy may be due to further unofficial releases.

It is estimated that today there are about 60 Eurasian beaver individuals in Italy. Eradication of the species was the first management option considered when the suspicion of unauthorized reintroductions was confirmed. But the permanent removal of beavers should be carefully thought through, and the ecological benefits of the return of this species taken into account.

Expansion and reintroduction of beavers: the rewilding approach

Beavers returned to Italy in two ways: through natural dispersal in the north-eastern regions of Friuli-Venezia Giulia and Trentino-Alto Adige, and because of illegal reintroductions in the other areas where they are present.

Mario Cipollone, as the Team Leader of Rewilding Apennines, states that: “The reappearance of a species in its previous territory is always a reason to celebrate. It is proof that when human intervention is minimal, nature is able to regenerate itself and find a way to thrive. This does not mean that reintroducing a species to its previous range, without having verified that the ecological, social, and cultural conditions of the landscape are able to support its development and that the causes that led it to extinction no longer exist, is the correct way to rewild an area. Even in the case of planned reintroductions the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) strongly discourages operations conducted without feasibility study and no genetic analysis of released stock, because of the damage that released animals may cause to native ecosystems”.

IUCN has developed clear guidelines (”Guidelines for Reintroductions and Other Conservation Translocations”) which are meant to be the backbone of any conservation and reintroduction initiative. They guarantee reintroduced individuals the best conditions to survive and thrive through a strict process of feasibility studies and analyses. In addition, to ensure peaceful coexistence, it is important to consider the possible impact that the species in question could have on human activities and vice versa. There are multiple tools, such as the European Wildlife Comeback Fund promoted by Rewilding Europe or the LIFE program of the European Union, which allow to contribute to the reintroduction of keystone species such as the beaver through a process approved by the scientific community, the government and public opinion. This is the only way we can ensure everyone’s collaboration so that the reintroduced species is protected, takes up its role in the ecosystem again, and can, over time, establish a healthy population.

Multiple beaver benefits

Whether it is for the construction of dens and dams or for foraging, beavers modify the landscape in which they live to meet their ecological needs and, in doing so, they provide important ecosystem services. Beavers support biodiversity by regulating hydrological flows and water storage: they reduce the risk of forest fires and floods, they mitigate the risk of droughts, and they trap sediments and pollutants. Beavers contribute to the restoration and creation of riparian and freshwater habitats: they boost the populations and diversity of invertebrates, amphibians, birds, mammals and fish, as well as improve the abundance and diversity of many plant species, and increase downstream water quality. In short, beaver activity has an enormous positive impact on biodiversity, ecosystems and water resources.

When people think of beavers, dams are often the first environmental transformation that comes to mind. Beavers also dig canals and coppice trees.

The Eurasian beaver is an herbivore that thrives in areas near waterbodies. It generally prefers adult trees belonging to the genera Alnus (alder), Fraxinus (ash), Prunus (cherry), Corylus (hazel), Acer (maple), Sorbus (sorb), Quercus (oak), Populus (poplar) and Salix (willow). By foraging on mature trees, beavers increase light in the lower levels of the canopy, reducing competition and promoting the growth of herbaceous plants and young trees.

Beaver dams may decrease peak discharge and stream velocity, which in turn reduces erosion potential and the possibility of flooding. They also expand riparian habitat and recharge groundwater by raising the water table. A series of beaver dams can regulate the flow of water throughout the year, reducing the risk of floods. Furthermore, each individual dam traps sediments and organic material and contributes to increasing the surface water level by creating small riparian areas rich in nutrients, such as nitrogen and potassium, and foster microbial activity and aquatic plants. Dams are also able to trap pollutants, increasing the quality of water downstream.

The area surrounding a beaver dam, with its slow-flowing water and lush vegetation, is very rich in microfauna, such as terrestrial and aquatic invertebrates, providing food for many animal species. Fish, amphibians, reptiles, and birds find plenty of food and the ideal conditions to reproduce. Large and small herbivores, such as hares, roe deer and red deer, feed on young plants in the warm seasons and on the bark of fallen trees in winter. Fallen trees also provide a perfect place for small mammals to nest and eventually lead to the regeneration of soil and organic matter. The high number of insects around waterbodies attracts bats, while the presence of amphibians, reptiles and small mammals attracts otters, known to often share the rivers with beavers. Finally, while adult wolves hunt large herbivores, the beaver itself is an excellent prey for younger individuals at their first hunting experiences.

Coexistence between beavers and humans

Although the number of beavers in Italy is still too low to cause significant changes in the rivers and landscapes, as its populations are slowly growing, we need to consider how to live alongside this keystone species.

As so-called ecosystem engineers, beavers play a crucial role in shaping ecosystems. Their activities are mainly limited to an area within 20 m from the banks of rivers and ponds. However, when humans also use this strip of land, the need for management strategies tackling human-beaver interactions might arise.

Beavers are very adaptable animals that have few habitat requirements. In countries where they have been reintroduced and a healthy population was established, they can have an impact on human activities by digging, debarking trees, and modifying the level of the water table.

When people think about human-wildlife interactions, they often express their concerns regarding possible damages on crops. Beavers can feed on crops, but the loss they cause to farmers is minimal. A more significant aspect is the impact of beavers debarking and cutting fruit trees and trees with economic value. The trees cut down can also become an obstacle impairing the drainage of rising river water, blocking access to fields and streets, or damaging power lines. The backwater of beaver dams can flood forests, agricultural fields, roads and house basements. The increased ground water level can clog up drainage pipes, increase banks erosion and destabilise railroad tracks. Beaver tunnels can also be dangerous for vehicles that could get stuck in collapsed tunnels and compromise the integrity of high-water dikes.

In many European countries where beaver populations are well established, several management strategies are adopted to promote coexistence.

A sustainable solution to human-beaver conflicts would be the end of anthropogenic disturbance in areas that beavers occupy, noticeably the 20 m land strip along the banks of water bodies. These areas would be of great value not only for the beavers and many other wild species, but also for people: they buffer fertiliser and pesticide drainage from agricultural lands, and they can be used as buffer areas to protect human-used lands from floods.

This solution may encounter resistance, especially in highly anthropized areas, therefore there are other management strategies that can be put in place, especially to protect trees with economic value and prevent beavers from digging under farmland. In countries like Germany (Bavaria), the Netherlands, Latvia, and Scotland, common mitigating measures include wire mesh, anti-game paint on tree trunks and economic compensation. Gratings, sheet-pile walls, or gravel layers are used to prevent the undermining of dams and roads; electric fences keep beavers out of chosen areas, and culverts passing through beaver dams lower the impact of flooding. Another common mitigation measure consists of carefully monitoring beaver populations and quickly individuating possible conflicts before they arise. Beavers identified as possibly problematic are relocated and dangerous dams are lowered or removed.

Local populations perception of wildlife species they live alongside is of fundamental importance for the success of a reintroduction. 1114 people from the Italian regions affected by beavers’ reintroductions were interviewed at the end of 2022 to assess their opinion on this matter. 65.5% were in favour of the reintroduction of beaver in Italy, and only 1.2% were strongly against it. When analysing the reasons behind negative opinions, the major reasons of concern where the effect that beavers could have on the riparian environment and biodiversity, and the lack of favourable environmental conditions, in terms of resources and space, to sustain a healthy beaver population. A clear correlation was shown between a negative opinion of reintroductions – accompanied by a positive opinion of the removal of already reintroduced individuals – and a lack of knowledge of the ecology and potential impact of beavers on the ecosystem.

Beavers can be an asset for local communities, providing ecosystem services that cannot be replicated, and attract wildlife-based tourism. Potential conflict between beavers and human activities requires management strategies that should take into consideration both beaver needs and human interests. Living alongside this species is not only possible but also desirable, and the changes that it will bring to the environment will benefit both nature and people.