Throughout Europe, the use of toxic substances to eliminate wildlife has its roots in ancient times when all those animals, especially predators, which posed a threat to hunting, livestock, and crops, were considered “vermin”.

The concept of vermin animals was completely abandoned starting from the 1970s, when predators were finally recognized for the crucial role they play in natural dynamics. Despite this, the persecution of many of them still persists today, carried out through various means, including poisoning.

This practice has persisted over time because, despite its devastating consequences on the ecosystem, it has been perpetuated by deeply ingrained economic interests and cultural expressions. Considered a convenient and economical method to control predator populations and other “unwanted” animals, the use of poison was not only legal but even encouraged. The royal decree of June 5, 1939, no. 1016 states “The killing and capturing of vermin can be done with snares, traps, and poisoned baits.” Few restrictions were imposed, except for some basic safety rules; otherwise, “the fight against vermin” could be carried out at any time and by any means.

The killing of these animals was therefore a real mission, as well as a profession. Manuals were even written with precise instructions on how to achieve the best results, such as “The Enemies” by Emilio Sheibler (1939) or Trapping: a practical manual for rational control of vermin, written by Edoardo Beni in 1970.

And it was not just the hunters’ task. Outside the hunting season, it was even entrusted to surveillance bodies. Even the park rangers of the oldest Italian National Park had this activity among their duties, which they often carried out using poisoned bait. Giuseppe Di Nunzio, a historical park ranger of the Abruzzo National Park, hired in 1954, recalls in an interview given to Luigi Piccioni for the essay “Nature as a profession”:

“We rangers also had to fight vermin. (…) At that time, what was rewarded were the fox, the wolf, the marten, the polecat (…) Then it changed completely, different scholars from different universities, in short, no longer accepted this way of considering these animals. (…) Then I became a ‘luparo’ (n.d.r. the term “luparo” means a person who by occupation is in charge of killing wolves) because the ‘luparo’ was not considered a poacher, then it was considered a profession, and the park gave you everything just to eliminate the wolves. (…) Then I arrived at the Park, I was very favored because I was already experienced.”

Undoubtedly, the historical and most illustrious target of poisonings has been the wolf, annihilated in vast European areas especially through strychnine. This predator underwent systematic and relentless persecution, where every single killing was rewarded with money.

Strychnine is an extremely strong poison extracted from the Strychnos nux vomica, a plant from Southeast Asia and India, which arrived in Europe in the sixteenth century through the Arabs. In addition to being one of the most toxic substances, it is also very resistant to decay, so it can persist for a long time in the environment. Today, the list of poisons used to eliminate wildlife has become richer and more diversified: pesticides, rodenticides, molluscicides, veterinary medicines are used depending on the context and availability in the illegal market. In many cases, these are substances for which trade and use are prohibited or severely regulated.

In addition to inflicting serious blows to the wolf, poison has caused the unstoppable decline of various species of scavenging raptors. Two species of vultures – the cinereous vulture and the bearded vulture – became extinct in our country also due to the massive poisonings they were collateral victims of. It was close that two other species would meet the same fate: the griffon vulture and the Egyptian vulture, which, reduced to small isolated populations, are only thanks to recent reintroduction projects vital again in Italy.

It wasn’t until 1977 that poison was finally made illegal, along with the use of snares and similar traps. The protection of the wolf triggered a real revolution. With the hunting ban on this species – first established in 1972 and fully regulated in 1976 – but above all with the new law on the discipline of hunting activities in 1977, the concept of vermin and consequently their systematic, planned, and legal persecution were definitively left behind. Moreover, the most important achievement with this law is represented by the transition of wildlife from the state of res nullius, meaning “nobody’s thing,” to that of res communitatis, “of the community,” namely the State’s non-negotiable property and therefore protected and safeguarded.

Despite these civilization achievements, born from the impetus of new knowledge in the field of ecology and a new environmental consciousness, the practice of poisonings has not decreased and shows no signs of diminishing. As often happens, the noble theory of regulations finds no space in practice. The backward push of those who march in the opposite direction to the progress of human thought and are indeed eager to return to systems and customs of the past is still very strong.

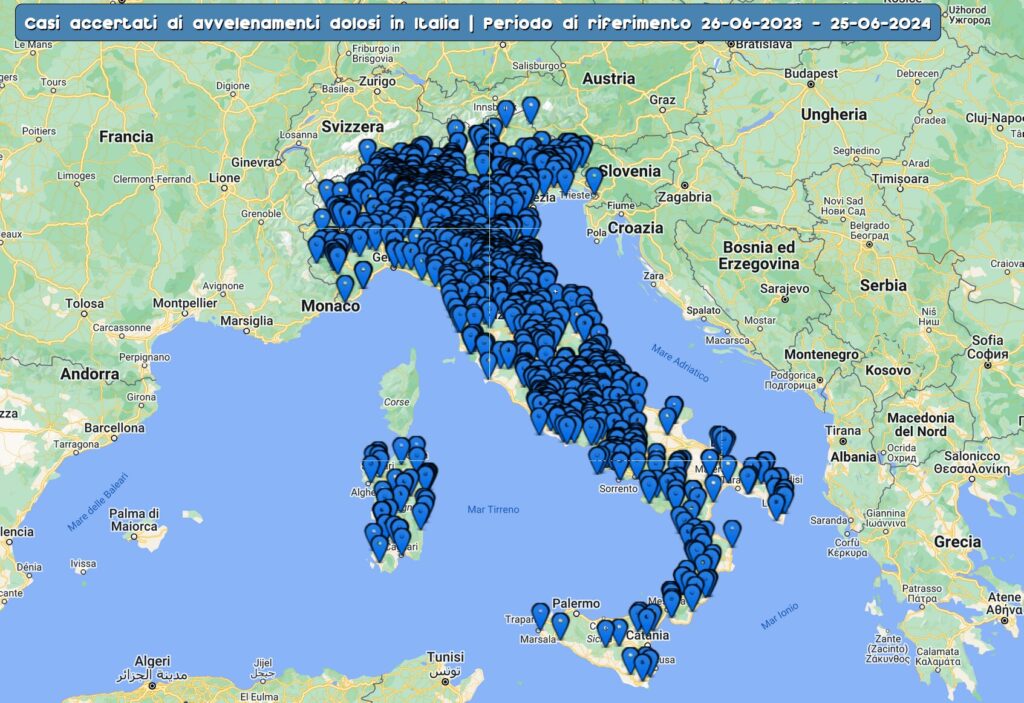

Looking at the map on the National Portal of Malicious Poisonings, one remains incredulous to see Italy entirely covered by dots marking the confirmed cases of malicious poisonings only in the last year, which have caused the death of hundreds of domestic and wild animals. In 2022, there were almost 1000, nearly 3 animals per day. However, especially in the case of wildlife, these certainly represent a strong underestimation of the real phenomenon because they depend on the animals finding. What is even more surprising than the impressive size of the phenomenon is the small number of people investigated or convicted for dispersing poisoned baits into the environment.

The ordinance issued by the Ministry of Health in 2008 seems to have been in vain, over the years renewed and up-scaled to the latest version in 2019, another very important milestone in the fight against this cruel and dangerous practice, which establishes times and ways of reacting to suspected poisoning cases. Only in Abruzzo, between 2009 and 2023, 1391 domestic and wild animals tested positive for poison, on average 53% of all those brought each year to the Institutes responsible for analysis, an annual average higher than that recorded before the ordinance.

Despite significant legislative progress and growing scientific knowledge, the fight against the use of poison to eliminate wildlife in Italy is still far from being won. The deep roots of this practice continue to hinder full compliance with modern regulations. It is essential that institutions and civil society intensify efforts to educate, raise awareness, and strengthen controls in order to effectively protect wildlife and ecosystems. Only through constant and coordinated commitment it will be possible to overcome retrograde resistances and ensure a future where harmonious coexistence between humans and nature becomes a concrete reality.