The poisoning of wildlife represents a cruel and criminal practice that we can no longer tolerate! Despite an Ordinance from the Italian Ministry of Health that details procedures in cases of suspected poisoning, reported cases rarely lead to effective investigations and convictions. Why can’t we completely eradicate this scourge?

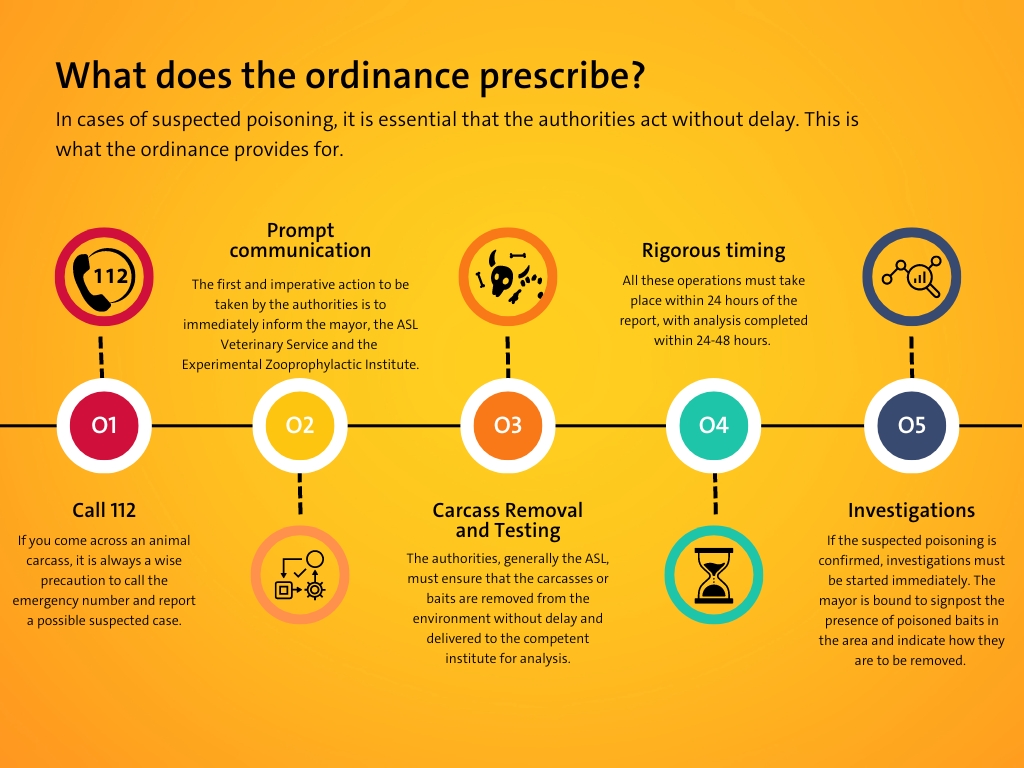

In the latest publication of our #LetsNotPoisonOurselves campaign titled “The poison: a bad story“, we discussed social and regulatory achievements against wildlife poisoning. One of these is the Italian Ministry of Health’s Ordinance Regulations on the prohibition of use and possession of poisoned bait or lures (2019), which establishes all necessary actions in cases of poisoning or suspected poisoning.

Today, this decree is the main tool we have to face this crime in Italy. But is it enough? It doesn’t seem so, considering the vast number of confirmed cases, with few criminals identified and even fewer convicted. What are the limitations of this tool then?

Regulatory and operational limitations

Although the Ordinance certainly represents significant advances in the fight against poison, it remains an extremely weak tool, subject to political will for annual renewal. A specific law on the crime of poisoning, currently absent in the Italian legal system, could better support both the work of the judicial police and the magistrates.

Moreover, the Ordinance does not expressly state that the scene should be treated as a crime scene – with the due scientific findings and investigative activity that this entails – further complicating already complex investigations. Poisons are of many types, acting in different times and ways, and when faced with the carcass of an animal, it is not easy to understand the spatial and temporal origin of the event and, consequently, in which area to direct the investigation. Not only that, the impossibility of finding the body of evidence – corpus delicti – often complicates and delays the very start of investigations, which should instead begin promptly even in its absence.

Several players are involved in case management, each with specific tasks and timeframes. While this ensures the necessary professionalism, it considerably complicates coordination among the various figures. Who then ensures that each task is completed? The activation of the National Portal for Malicious Animal Poisonings, which monitors and digitizes cases in real-time, can certainly support coordination, but central “direction” is lacking.

The effectiveness of actions could significantly increase if supervision were entrusted to a single highly trained entity in this type of crime. The set-up of Anti-poaching Investigative Units, similar to the Forest Fire Units, could be a winning strategy. Similar experiences tell us this: for example, Forest Fire Units – part of the Carabinieri Command of the Forest, Environmental Agri-food Investigative Units – over time have gained unmatched expertise in fighting arsons, precisely due to their high specialization in this crime. Significant investment in advanced training, as well as adequate financial and human resources to the scale of this crime could also increase the chances of using innovative tools, such as molecular and genetic techniques and forensic veterinary science, to identify the offenders.

Finally, developing memoranda of understanding between the judicial police and wildlife monitoring agencies could prove to be a key tool for investigations. GPS-tagged griffon vultures monitored by Rewilding Apennines and the Carabinieri Biodiversity Unit of Castel di Sangro, for instance, have often proved to be the first “sentinels” of poison. By analysing their movements, it is possible to understand when one of them dies and whether their death is linked to the consumption of poison and, thus, better direct investigations.

Raising awareness

It is also essential to raise awareness among the Judiciary. Indeed, while investigations need to be conducted correctly and thoroughly to provide a useful framework for the magistrates, it is equally important that magistrates themselves are well aware of the severity and danger of this crime, whose consequences do not stop at the targeted animal but extend collateral damage to other species, the environment, and humans.

The occurence of dumped poisons or toxic substances in the environment – reads the Ordinance – poses a serious risk to the human population, especially children, and causes environmental contamination. In the last 20 years, nature tourism has grown exponentially worldwide, and the central Apennines have been no exception. The number of hikers is much higher than in the past, and since poisoning cases show no sign of decreasing and occur mostly in placesthat are accessible to all, the chances that people, including children, and pets come into contact with the poison significantly increase. Some very strong poisons, let us remember, can cause severe health consequences, even death.

The question is whether we have to wait, as often happens, for a human to die before taking this crime seriously or whether it is time for it to become an absolute priority to protect not only wildlife and the environment but also our own safety.